Interview

“It Sounds Pretty Stupid”

Jerome Tanon And The Eternal Beauty of Snowboarding

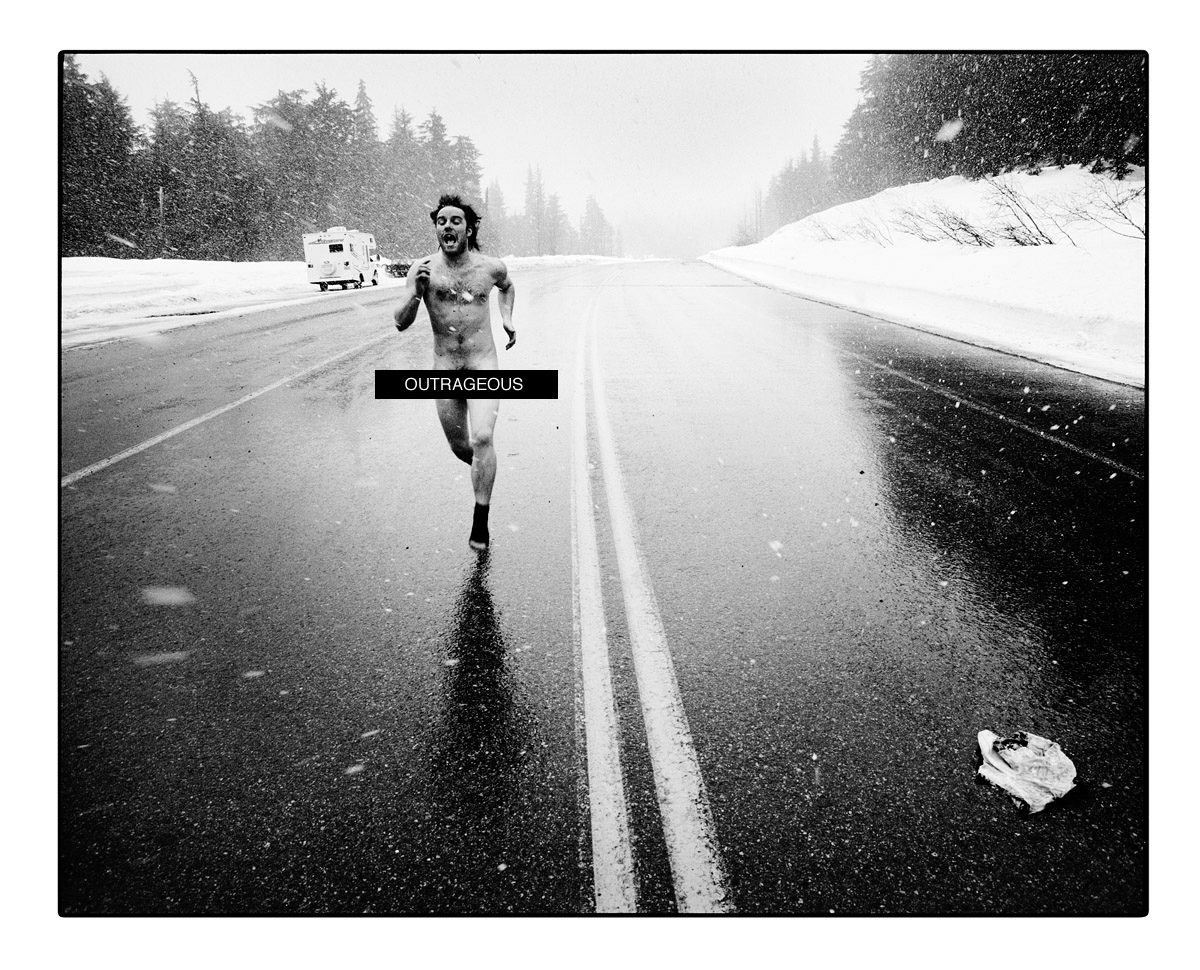

French photographer Jérôme Tanon is an anomaly. In a digital world, the 30-year-old Annecy resident keeps it analog. He chooses to undertake the time-consuming (and expensive) process of shooting, developing, and printing his work the old-fashioned way on film. Then, perhaps a bit ironically, he has to scan the damn things too. But shooting film gives Jerome a personal satisfaction that can’t be found when dealing in the digital realm—there’s more room for experimentation, surprise, and a timeless quality to the physicality of the endeavor.

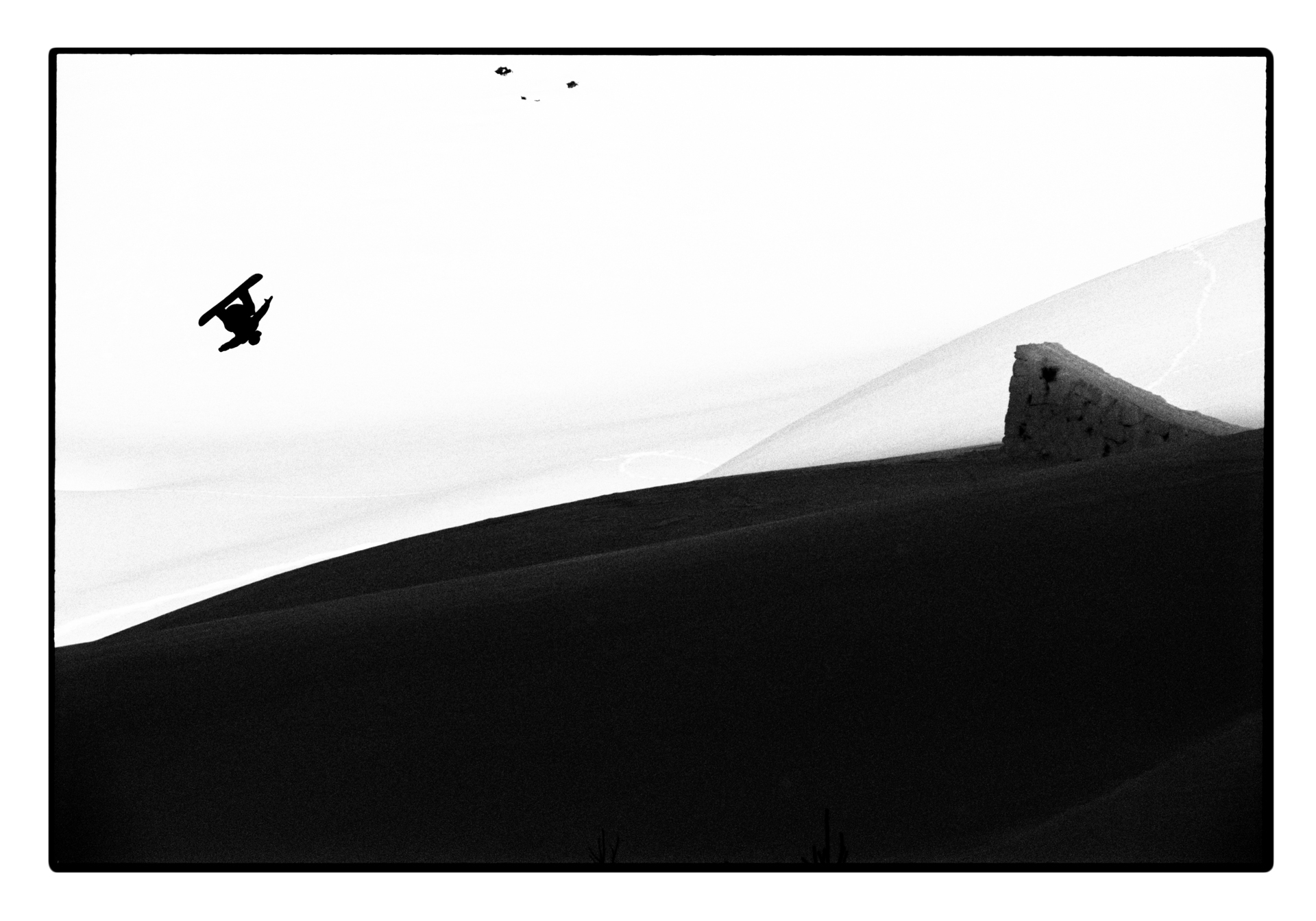

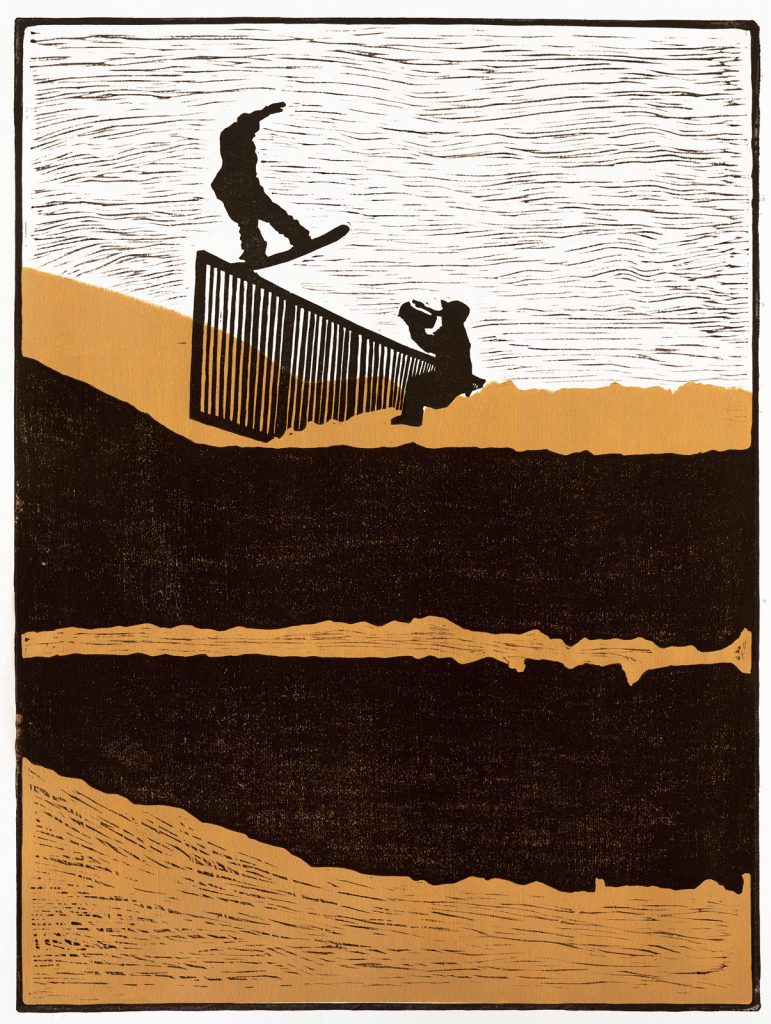

You’ve seen Jerome’s imagery featured prominently in our pages for the past six or seven years—his black and white work, etchings, various printing processes and eye for the in-between moments speak volumes about what carries us through a season, a decade, a lifetime on snow.

Given his labor-intensive approach, when Jerome strapped a digi camcorder to the top of his assortment of SLR’s and began recording, many questioned whether the project would come to fruition. Traveling with the best film crews in the business—like Absinthe Films—he became a new kind of documentarian.

When he dropped a four-minute teaser this spring, we knew that something unique was coming. And this fall he toured “The Eternal Beauty of Snowboarding”—a 45-minute film that provides a raw and sometimes hilarious look into the process of riding and documenting time in the mountains for mass consumption. It asks whether there is intrinsic value in the pursuit—are pro riders and their incumbent media entourage simply hedonists who are only chasing snow for self-indulgent reasons? Or is it something deeper than that? Maybe the answer is a bit of both. Gather a few friends, watch the movie and decide for yourself. At the very least, you’ll share a laugh via this refreshing and raw take on the global migrations we undertake in order to provide something fresh year after year.

Jerome recently premiered his film in our hometown of Bellingham, WA. He paid for the theater himself and showed it for free. The next day, he stopped by the office and we discussed his labor of love.

ABOVE Sage Kotsenburg and Blake Paul. Photo: Tanon.

The Snowboarder’s Journal: Why make this movie?

Jérôme Tanon: I was waiting for someone to do this behind-the-scenes, real life take on snowboarders, and criticize what we’re doing a bit—try to put our feet back onto the earth, because we present such an image of heroes and badass dudes [in snowboard media]. No one did it, so I decided I had to do it myself.

I had no idea how to make a documentary. It’s my first movie. But now that it’s all together and makes sense and has all the funny shit I expected it to have, I’m just sitting in the corner and giggling every time I show it.

I also used this movie to answer personal questions I have all the time like, “Why am I shooting snowboarders? Why am I spending my time doing this? Should I try to find a good reason to do it, or should I try to understand better why I do it, and also try to share the passion?”

I love snowboarding and snowboard photography, but not everyone does. It’s like you’ve got this song that you love, and you want to share it with a friend, but you have to explain to him why you love this song so much. If you just say, “Hey dude, listen to this song it’s awesome,” he’s going to be like “Eh, whatever.” But if you explain it to him like, “It’s because the lyrics come from here, the music comes from there,” then he’ll understand it more. It’s the same idea. I want to explain everything that’s behind the shot, all this work that we have to go through, what goes through the snowboarder’s mind, why he builds the same jump as the year before.

Then when you see a snowboard video or photo, you can appreciate it more. The beauty is also the theme of the movie; you have to point out beauty to someone who doesn’t find something beautiful in order to make him see the beauty. Not everyone sees beauty in everything—some people see beauty in trees, but I don’t see beauty in trees. Should I? If someone who was totally into trees would explain to me how and why a tree is so beautiful, I’d probably find a tree beautiful.

ABOVE Nils Arvidsson, fakie miller flip double exposure. Photo: Tanon.

ABOVE Nils Arvidsson, fakie miller flip double exposure. Photo: Tanon.

Are you trying to access an audience that’s not your core snowboard consumer and engage people who don’t quite get it?

That’s definitely the idea. Of course snowboarders are going to have a good time watching the movie because they can relate to it. But I know I can show this movie to my parents and try to explain to them why I’ve been doing this for years. My parents can tell that I like snowboarding, but why should I spend that much effort on taking photos of dudes jumping in the air? It sounds pretty stupid. And that’s why you have to find a good reason to be in the snowboard industry, to be a snowboard artist.

ABOVE Jerome in Alaska. Photo: David Vladyka.

Do you think you answered that question of “why” for yourself?

I started writing the script by asking myself the same questions, but I didn’t have any answers yet. I didn’t want to have one. The fact is that these dudes are so amazing in a way, they have such cool personalities, they’re all very unique, they’re so different than the average person, and that’s the best part about snowboarding. In the end we’re super self-centered, but still there’s something in there that’s beautiful and pretty interesting to see, and it’s worth documenting.

ABOVE Lucas Debari, frontside 360 with Shane Charlebois filming for Absinthe Films. Champery, Switzerland. Photo: Tanon.

You kind of justify your own existence.

Exactly. I was trying to justify my own existence, because some days I would ask, “Why am I here? Should I not be doing something else? There are so many things you can do in life, should I spend all my time shooting snowboarders?”

ABOVE Tyler Chorlton, backside 1080 double cork. Photo: Tanon.

And the answer was yes?

Yeah. But it’s been 10 years that I’ve been doing this, and since this film is sort of an artist’s statement about why I shoot photos this way, I feel like it’s closing the circle I started 10 years ago. I don’t want to repeat the same photos over again and over again, I don’t really see the point. Some photos I took six years ago still make me proud, like “This is still a good photo today.” I don’t feel like I have to go next year and the year after. I’m going to go because I love it, not because I have to. If I wanted to move on, I feel like I could now start doing something else with my life.

ABOVE Fredi Kalbermatten, frontside 360. Photo: Tanon.

You spent three years filming while shooting photos at the same time. How did you achieve that?

That was the hard part. Most of the snowboarders that I was hanging out with the past years, they didn’t believe the movie was ever going to happen. I filmed with a $200 Sony handycam glued to a flash mount then attached to the hot shoe on my camera. So I was taking photos and pressing record a little before the guy would drop—trying to focus on making good photos but also make sure the camera was framed right. I ruined the camera along the way and bought another one, exactly the same.

My photos take a lot of time because I have to develop them when I get back home, I have to scan them, go in the darkroom, it takes five times more than if I was shooting digital. So every night during the winter I would open my computer and work in Photoshop. I stored the footage on a hard drive and never looked at it.

Last summer, I decided that if I wanted to make this happen I’d have to look at the footage and make a trailer. And if the trailer got a good response, it would give me the pressure I needed to make the movie. People liked the trailer so then I had pressure to make the movie. The editing took so long because I had such a huge pile of shots, more than 200 hours and 13,000 different shots.

What’s the main thing you learned through the creative process?

When you start filming a documentary, you’re mostly filming yourself. Even if you’re pointing the camera at your friends you’re asking yourself, “What are we doing right now?” We would be building a jump forever, and just the fact that you take the camera out means you’re not an actor, you’re a spectator. You’re now there to think and take a few steps back, literally. And that’s the step back you need in order to answer, “What are we doing here?” By filming I’m not just a photographer any more, I’m a witness and by my voice and my video editing I can talk to the whole world, and I’m going to be a live reporter from the scene.

ABOVE Tanon and his setup. Photo: Andrew Miller.

You went on tour with Absinthe for the first handful of showings. Did the crowd react how you expected?

It was way different than what I expected. People were laughing their asses off, so much more than I thought they would. You probably laugh more if you’re in a crowd than if you were watching this alone on your computer—when your neighbor is laughing, you laugh more. I also found that sometimes when there was a joke going and I’d expect people to laugh during the joke, people would actually laugh right after the cut to the next scene. That’s not something I expected at all, it’s something I just learned by watching the crowd.

I tried to put room in the edit, but most of the time they were still laughing when the voice-over came in. You almost have to make two edits—the web edit wouldn’t have as much time because you can’t expect people to be laughing for three seconds after a joke by themselves.

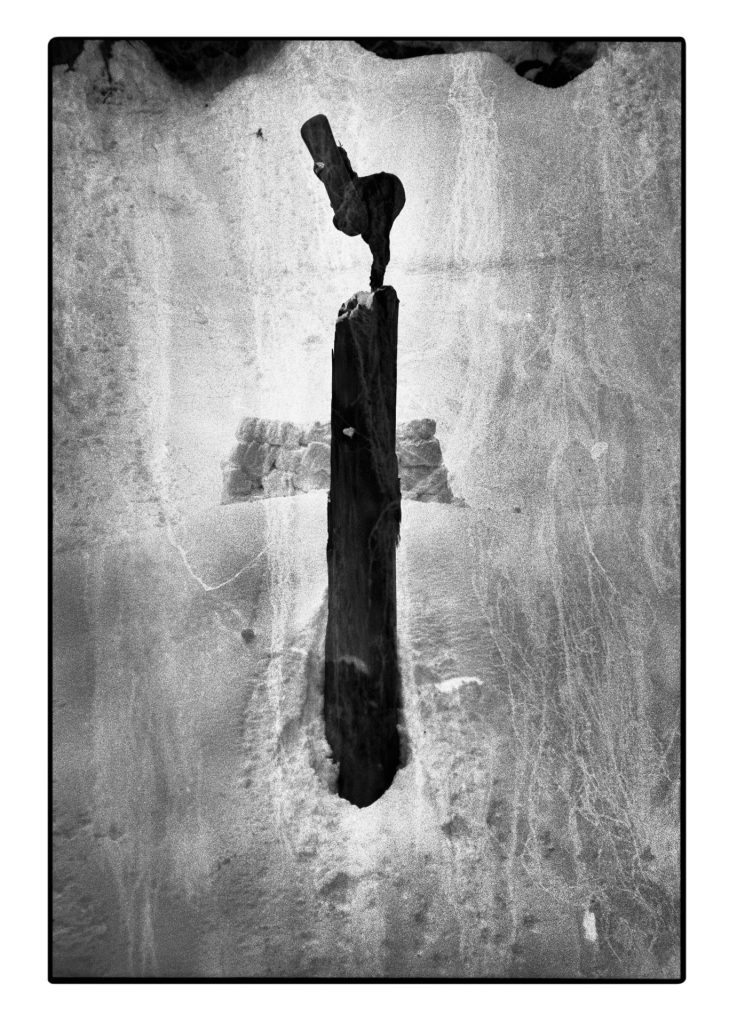

ABOVE Etching of Louif Paradis. Art: Tanon.

You showed some edgy stuff in the film. Did you have to ask the riders’ permission?

I have to thank all the guys that I’ve been hanging with, these riders and videographers. I didn’t even ask authorization to film them or to display them in weird situations. I did ask the riders who have some controversial footage in the film while I was editing, “There’s you kissing a girl, doing this or that, are you cool with this?” And all of them replied, “Yeah dude, go for whatever you need to say. We’re backing you up.” Even the guys who have heavy energy drink contracts that are displayed in a section where I talked about that. They mostly agree with what I’m saying, it’s just that they can’t be saying it themselves. But since I’m saying it, it’s not their responsibility.

ABOVE Emilien Badoux, Haines, AK. Photo: Tanon.

That’s interesting because you’re showing a more real side of snowboarding, whereas energy drink companies and others are really pushing that hero image—the super serious snowboarder.

I feel like if you really want to love something, you need to know the bad side of this thing. If you have a girlfriend and she never shows you her bad sides, you can’t really love her in a full way. It’s the same here: you can’t love snowboarders if you have this fake image of them. Once you find out that they’re humans, that they’re wacky and stupid, maybe you love them more. Maybe they could be your friends, any of your friends.

ABOVE Janne Lipsanen (air) and Victor Daviet (igloo). Photo: Tanon.