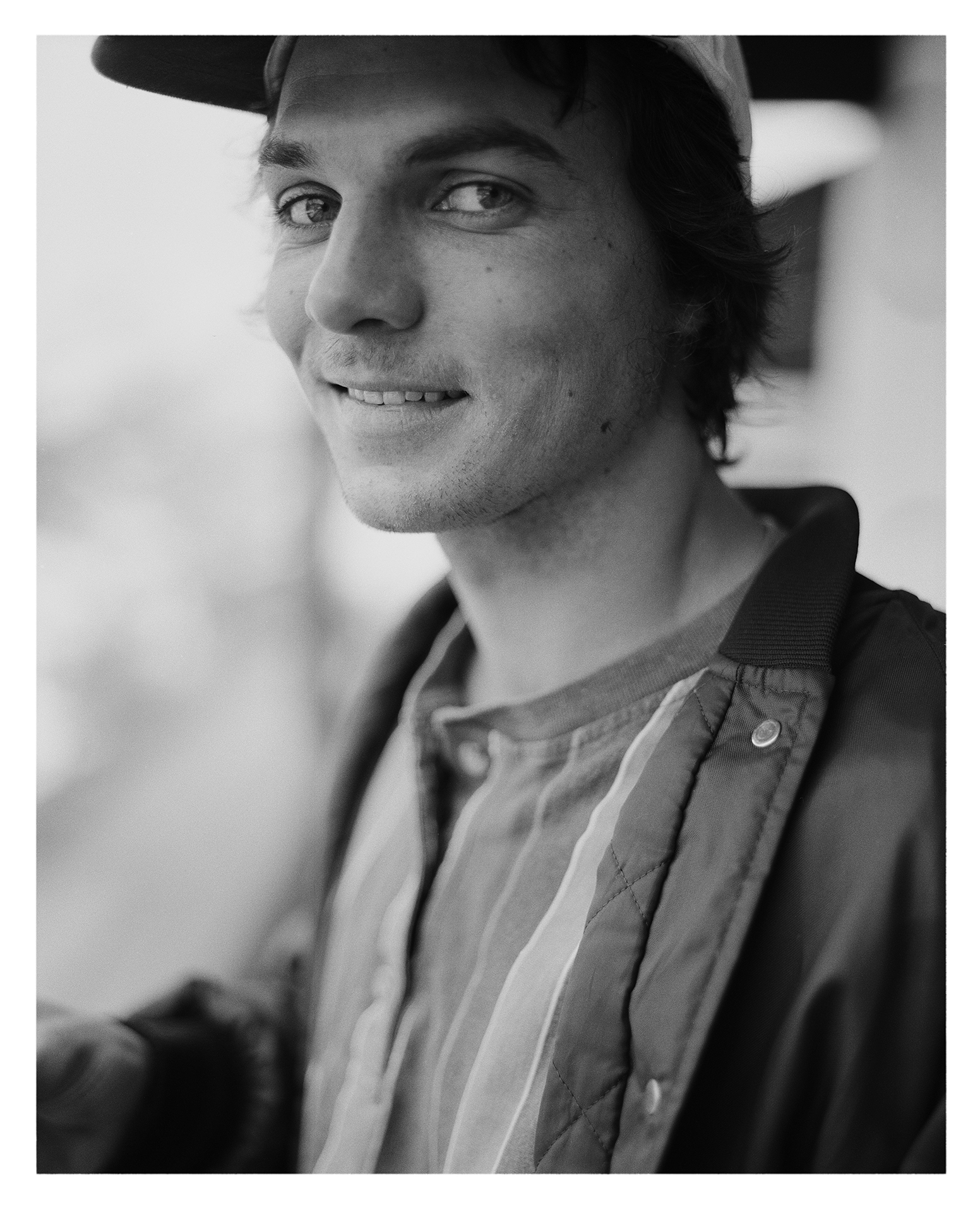

Profile

Keegan Valaika

Pure Intention: Keegan Valaika and Something Unpredictable

This article first appeared in The Snowboarder’s Journal Issue 15.4.

“Maybe it was just that I was able to create an atmosphere which destroyed people’s customary expectations, an atmosphere in which miracles could flourish. Anyway, it spooked the hell out of me. I even managed to spook a few doctors and nurses. That’s impressive spooking, considering the extensive spookproofing those people go through and all the antispook drugs they pumped me full of.”

-Mark Vonnegut, The Eden Express: A Memoir of Insanity

Keegan Valaika has been through some shit. That’s the short of it. Keegan, who is 28 now, says he could write a book about it all. Exactly what he’s been through, nobody other than him can fully know. But, he talks about it some. Five years ago, Keegan had a mental breakdown. At the time he was living in Glacier, WA and partying a bit too much. He returned to his home and family in Laguna, CA for treatment. He read a lot during his recovery and really connected with Mark Vonnegut’s memoir, which details a psychotic breakdown and his subsequent recovery. That’s what Keegan went through. Is still going through. He’s doing better now. He’s still at it.

But, that’s just part of his story. After all, he’s been getting paid to snowboard since he was 15. We should all ride with such abandon. Dude makes it look easy. And there’s an element of improvisation to his riding. It’s unpredictable; engaging.

It started in a sort-of-fairytale way: Keegan won the Hot Dawgz and Handrails jam at Bear Mountain, CA, in the fall of 2004, and was quickly offered a contract to snowboard professionally. He was on his way. And that’s the way it went for a while. He chased winter, travelled the world, filmed, partied, rinsed and repeated. Eventually, there was a falling out with a sponsor. Money was left on the table. Then there were new projects. Ender parts. The Givin movies—three of them—which he made in conjunction with Aaron Hooper and friends. The Gnarly clothing brand, which is still going strong. More standout video parts.

Now with Brown Cinema, Keegan’s driving. He’s in control. He does what he wants. He worked hard for this freedom and he’s grateful for it. He’s never been more grateful for snowboarding. But he’s been through some shit. And here’s his story.

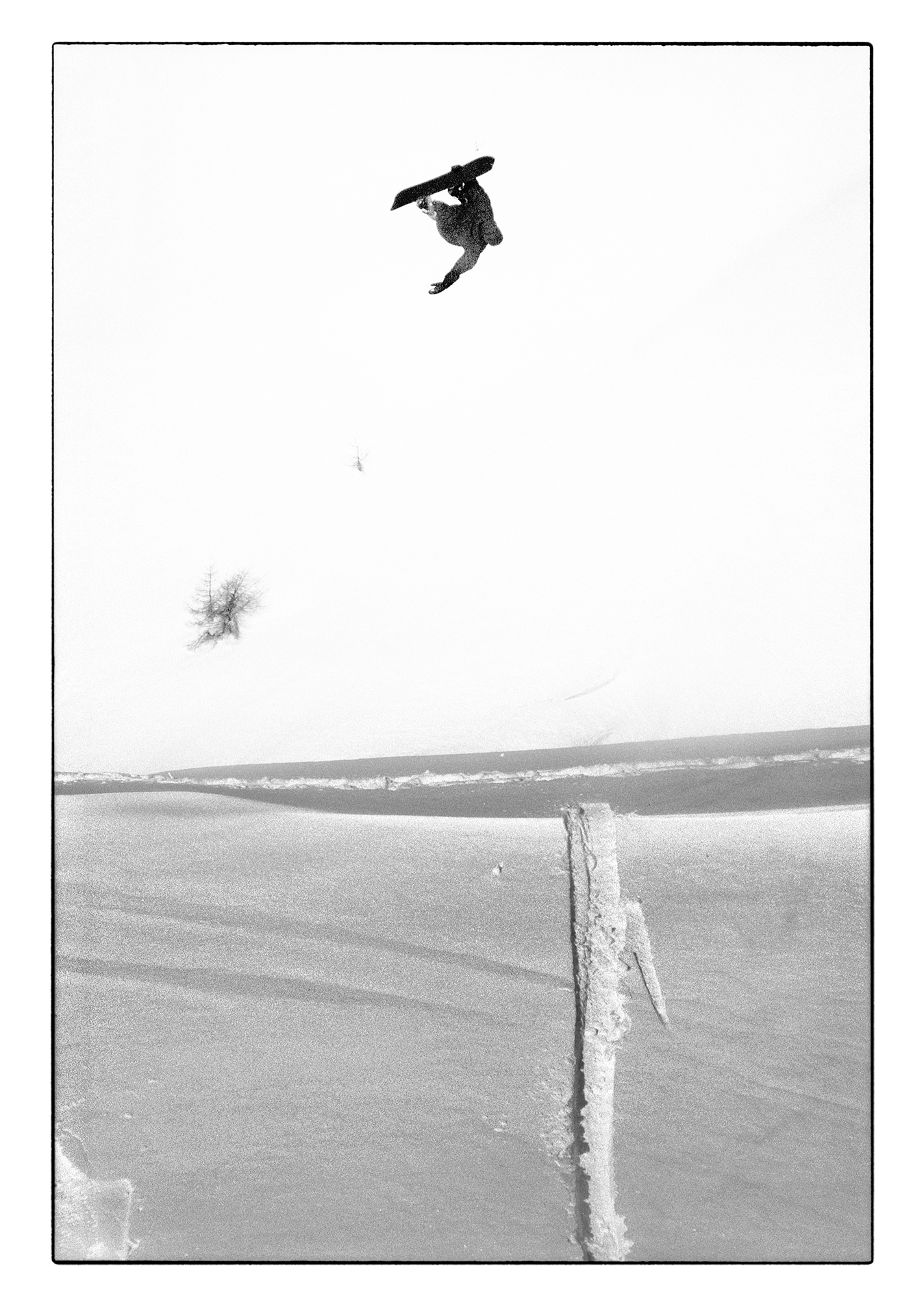

Zen moment in Mongolia. Photo: Bob Plumb

The Snowboarder’s Journal: When was your first day on the mountain? Were you skiing or snowboarding?

Keegan Valaika: I skied first. I think I was three or four when I started skiing. We were living in Telluride, Colorado. I was eight when I first saw people snowboarding. My dad was snowboarding. I remember thinking, “Dude c’mon, let me do that too.” But, they couldn’t get boards and bindings small enough, so I rode my Dad’s board at first, with ski boots in the bindings. We’d cinch the bindings down as tight as they could go. I was pretty much standing on a plank and just going straight down the hill, but it was awesome.

I’m surprised your Dad was snowboarding before you. So many of our parents were skiers.

Well, he did both. Snowboarding was a new thing at that time and he was just starting out too. I remember learning together. He could do 360s and then one day I did a 360 and he was like, “Shit, you caught up to me.”

Were you born in Colorado?

No, I was born in Newport Beach, California. I lived in Laguna and moved to Telluride and then we moved back and then back again. We were bouncing back and forth between Laguna and Telluride my whole life.

Salt Lake City, UT, 2008. Photo: Bob Plumb

Was it a job that kept your family moving?

My dad’s business kind of took a dive and at that point Telluride was a pretty cheap place to live. It was a hidden gem. So, we bailed and I don’t think he worked for a year. They had saved some money and we were just living the mountain life, ski-bum style. Then a couple years later when my dad’s business started doing alright again we moved back to Laguna. Then after a couple years he started really missing Telluride and we went back. My parents have always been adventuresome mountain people, but Laguna Beach is a really nice place. I think they like both and depending on where business was and where they were in life, they just chose between those two.

Best of both worlds and cool exposure to different cultures and environments for you as a kid.

It was really cool. Our parents would just drop us off at the beach and that was day care. They’d go to work at 8 a.m. and we’d stay at the beach all day, until dinner.

What do your parents do for work?

My mom was at McDonald-Douglas working on the space station as an engineer, but she stopped when I was born. My dad sells commercial real estate.

Where did they meet?

Stanford or somewhere in Palo Alto. That’s where my mom was going to school and my dad went to Cal State [University,] Fullerton. They were both gymnasts. I think my mom was dating my dad’s friend at first, and then she ended up marrying my dad. It seems to be the way it happens a lot of times. They’re still homies and there’s no bad blood or anything.

Sapporo, Japan. Photo: Austen Sweetin

And you still live in Laguna full-time?

Yeah, I have a house in the Canyon, near where [psychedelic pioneer] Timothy Leary used to live. My neighbors always joke that there is a bunch of acid buried under one of these houses. There is this book, Orange Sunshine, it’s all about the early 60s and late 50s, when Laguna was getting settled. People hung out in the canyon and for the most part it was kind of an artist colony. They had festivals. Jimi [Hendrix] and Janis [Joplin] played here.

Describe Laguna to somebody who’s never been there.

It’s kind of a bubble because there’s only the canyon road that comes in. It’s a sweeping, narrow two-lane road that’s pretty dangerous, actually. That’s the only way in unless you come from Newport or San Clemente or Dana Point. It’s a little less blown out than towns like Newport, where the freeway comes right into town. My favorite part about it is the coastline. It’s like Northern California, there are these big cliffs and they jut in and out. There are crazy rock formations and are all sorts of cool underwater caves to swim through.

And up Laguna Canyon it feels kind of rural.

Definitely. I’m tucked up against the mountains. There is one house in between me and the big hill and I can’t see anything else. There are tons of huge trees around here. One fell on my neighbor’s Jacuzzi not too long ago and destroyed it.

Everyone who lives in the canyon is really communal. Between my neighbors there’s a glassblower, a ring maker and three or four general construction dudes. So, when something like that happens, the neighbors come together and are like, “Oh, I’ll help you out. Here’s some beer. Let’s fix it.”

Untitled, 2017. Art: Keegan Valaika

Art is one of your outlets, right?

It’s more therapeutic for me. It’s another way to get into that place that you get with exercise or snowboarding or skating, when you’re really focused. You can’t think, your brain just goes to nothing, you’re kind of floating and time just flies. That’s why I really like painting, because I can get there with it. It’s more meditative and therapeutic than anything else.

Would you say the same about playing music?

Music is the same. There are days I’ll want to pick up the guitar to get to the place of quiet, but it’s just not working. Then I get frustrated and try something else and sometimes that doesn’t work, so typically I just go down the list of things I try when I’m having a day like that. But, those days come less and less often as I get older. Maybe because I’m more content.

It requires real presence of mind, which seems harder and harder to achieve these days.

There’s so much shit going on, my brain goes nuts sometimes. At this point in my life I’ve found enough ways to quiet my mind or control my thoughts. I can get a peaceful state of mind going and then sit in that state for as long as I can. Sometimes it’s easier than others, sometimes you can’t even get there. And with painting you’re dredging up feelings. It’s an active way of going in. Not only that, you’re going to dig those feelings up and put them on the canvas in front of you. And the more that canvas starts to look like you feel, the more you feel like you’re really getting somewhere. It’s almost like getting to know yourself.

You’re clearly deliberate with your thoughts and actions. Have you always been this way?

Well, it’s not like I’m aware of how I’m feeling at all times, you know? Sometimes I get caught in a fit or whatever, and it sucks. I just try and catch it when it happens and bring myself back. There was a big turning point when I had to be put on some meds. I hated it and pretty much wanted to die. So, I made a decision to get off that shit. I had to take a huge look at myself and be like, “Alright, now it’s on you. If you can’t control it no one can.”

It just requires extreme attention to detail within myself. To be able to be aware of how I’m feeling at all times is very important, so I guess that was probably the point when I started really paying a lot more attention to how I feel at any given point, you know?

There’s not much more to say without going extremely in depth, without writing an entire book. So, what I will say is: I think most diagnoses are complete bullshit and not everyone is the same. You shouldn’t call every kid A.D.D. because they’re a little antsy. There’s a deeper thing there, you’re not getting to the root of whatever it is. I think America is heavily over-diagnosed and it’s mostly due to medical companies and shitty doctors just looking out for number one. It’s a selfish kind of world we live in. It’s sad, but it’s a reality.

My girlfriend just got diagnosed with cancer and we’ve been in and out of the hospital a lot lately, and even there I can see it in small ways. We’ll meet with a doctor who’ll tell her she needs one thing. Then we’ll visit a cool doctor and he’ll say, “Actually, that’s the new one that they have all the marketing behind, so all the doctors are trying to push it because they get incentive.”

Front board, 270 out, Japan. Photo: Dominic Haydn Rawle

Can you talk about what it took to get yourself off medication? Is that where you’re at now?

I read a lot. I’ve always been really into Kurt Vonnegut and I somehow stumbled across his son. His son went through something similar to what I went through. His name is Mark Vonnegut and he wrote a book called “The Eden Express: A Memoir of Insanity.” It’s about his journey through, you know, talking to aliens and shit, and coming out the other side.

When I decided I had to get off the meds, I thought, “This might not work, but, fuck it, because I can’t live this way anymore.” And I was able to do it. Suddenly, I felt like I had all this energy again. I could skate. I wasn’t three steps behind my body anymore. Everything was coordinating and listening to my brain again. It was euphoric. And now, I just have to do my best to be aware of my moods.

You’ve got to do whatever you can to stay healthy.

It all comes down to health and taking care of your body. They say your body is the place you start from, that’s your vessel for this weird thing we call life. You gotta keep that thing in tip-top shape.

Especially as somebody who is so in love with being active. Have you found that skateboarding and snowboarding became therapeutic as well?

Yeah, definitely. They were always therapeutic activities, but I guess in a way I didn’t give them the reverence I should have. I didn’t treat them as sacred as they are. I was taking them for granted. And once I realized that, I just started doing them differently and treating them with more respect. I want to make sure my intent is pure, because the act of riding down a hill on a plank of wood is as pure as it gets. You’re flying, basically.

Back 7, Switzerland. Photo: Jerome Tanon

And you’ve been getting to do this for most of your life. Thanks to snowboarding, you’ve traveled the world since you were 15.

I’m a weirdo, because I’m more comfortable in other places than I am at home. I don’t feel like I really have a home. Laguna is where I like to be, but I’m really the most comfortable on the move. Traveling is what makes the most sense to me. I’m not good at, you know, having your local bar you go to every week or having the same people you always hang out with. That is really hard for me to grasp. Sometimes I think maybe I missed out a little bit on school or that aspect of life, but I wouldn’t want to trade in all that I’ve learned by traveling all the time.

It’s really eye-opening to experience different cultures at a young age. Snowboarding has given me so much to be thankful for, and it just so happens that snowboarding is my vehicle to travel to all these crazy places for free.

And you’ve been traveling with Brown Cinema lately?

It’s basically our perfect snowboard world. We’re doing it the way we want to. Evan Lefebvre at Adidas really had our back and hooked it up with enough money to get Butters (Brock Nielsen) to film. We got Scott (Blum) and Harrison (Gordon) to come along and we went to Japan. We didn’t have anybody telling us where to be or what to do. We just did the whole thing ourselves.

Butters filmed and whoever wasn’t snowboarding would film a second angle. It was a very natural style of snowboarding, I guess. Like filming a movie, but not writing any script. You kind of roll into it. It’s like jazz. You never really know where it’s going next, until you’re there and then you go somewhere else. The excitement of that, the element of surprise, tends to produce fruitful endings. You can almost feel the energy.

Photo: Jerome Tanon

It seems like you’ve always kept snowboarding strictly on your own terms, whether with projects like Brown Cinema, or Givin, or when you walked away from sponsors and pay checks. Not a lot of snowboarders would be as bold or as dead-set in their ways. Is it stubbornness? Where does that come from?

My dad’s the nicest dude and he’ll give everybody so many chances, but he’s also like, “If you don’t respect me, I’m not going to respect you.”

I always start with full respect for anybody right off the bat, but if you try to play me like a chess piece, then that pisses me off. I’d rather work at the shittiest job than have one where someone thinks they own me. Freedom is a lot more important than money at the end of the day.

And that’s the situation you’ve created for yourself with snowboarding, it’s a job, but you don’t have that many “bosses” to answer to.

Yeah. I have it about as good as I’ve ever had it, or I’ve ever known anybody to have it. As far as complete freedom, there are still days when I have to put on a pink jacket, maybe once a year. There’s a degree of compromise I have to make, a degree I’m willing to accept. But, I just draw a line—I can’t tell you exactly what that line is, but I know it when I feel it.

Plus, when you turn the thing you love into the thing you do for work, there’s this trade off. There’s an Oscar Wilde quote, “Each man kills the thing he loves.” It seems like you’ve tried hard to steer clear of that scenario.

I have a friend who always says, “Hold on loosely, but don’t let go.” It’s from an old rock song. It really resonates with me. If you squeeze it, you’re going to kill it.