Interview

Spencer O’Brien

First Steps: Spencer O’Brien’s Awakening

First published in Volume 20, Issue 2 of The Snowboarder’s Journal

Spencer O’Brien looked hesitantly at a pile of puppies up the back hill of Alaska Heliskiing’s compound at Mile 35, Haines, AK. Their mom was a big, white, shaggy dog who lives there. The dad, unknown. Spencer was hooked.

A little black ball of fuzz left the crate and waddled over. She named him Buns after her first ever run in Alaska, Canadian Buns. A ridge draped in pillows and spines, it’s a heavy intro to AK, but she’d ridden it fluidly and gone back for more, channeling powerful edge control and steadfast confidence built through a decade competing at the highest level of slopestyle and big air. Not a typical career path for someone hailing from tiny Alert Bay.

“Spencer’s first-ever run in Alaska, near Haines in April 2022. This line is in a zone called Canadian Buns—it’s where her dog got its name. Spencer was a natural in AK. She dropped first and rode fluidly top to bottom, no warm-up necessary.” Photo: Colin Wiseman

Off the east coast of northern Vancouver Island, BC, Alert Bay is an ocean-bound hamlet in logging country. But there was a little co-op hill nearby called Mount Cain, where Spencer learned to ski. As did her older sisters, Meghann and Avis, who got on board when they were young—the former had her own lengthy career as a professional snowboarder. And there was her dad, Brian, who enthusiastically backed the girls’ on-hill pursuits, moving them to the mid-island town of Courtenay for better access to organized sports, then followed Spencer to Whistler when she was in the 11th grade. That’s when she got an agent after landing on the podium at the US Open Rail Jam in 2005. By 2008, Spencer was a legit slopestyle threat, winning bronze at X Games. What followed was a decade of singular focus on pushing the boundaries of competitive snowboarding, and Spencer defining herself as one of the most talented and influential contest riders of her generation.

She traveled the world and went to two Olympics (Sochi and Pyeongchang in 2014 and ’18, respectively), finally earning X Games gold in 2016 after multiple podiums. That’s the CliffsNotes for contest Spence, a straight powerhouse in the public eye for much of her adult life. But behind the curtain all those years was Spencer the Indigenous woman from backwoods Canada who never really examined her identity, her culture, her family and upbringing, until recently, when she left competition and stepped into backcountry riding. Who battled injuries and illness and quietly pushed forward, always preferring to let her snowboarding do the talking. Who gambled on herself once again with the recent release of Precious Leader Woman, a biopic of sorts, that documents the process of Spencer letting go of competitive tunnel vision and discovering a side of herself she’d never truly explored for 30-plus years.

There, in Alaska, Spencer was still, as she says, “taking the first steps” toward a new path in life, in snowboarding—one with more balance, more family, more vulnerability, more growth, more big mountains, more time to reflect. Now 34 years old, backcountry Spence has a lot left to give—as a rider, as a person.

In July, we caught up in Ucluelet, BC, where she was renting an apartment from Robin Van Gyn and Austen Sweetin for the summer. Buns was wreaking havoc, growing into his lanky frame. But we found time to talk during an idyllic afternoon on the porch overlooking the harbor. Not about Spencer the competitive rider, but about Spencer the person. About heritage, health, family, growth, voice, vulnerability, and the importance of leaving it all on the floor.

“Spencer and her dog Buns in Ucluelet, July 2022, shortly before we sat down for this interview. She was living in an apartment at Robin Van Gyn and Austen Sweetin’s property with a big, old boathouse that functioned as a natural lightbox and provided a nice, warm glow.” Photo: Colin Wiseman

The Snowboarder’s Journal: You are the mother of Buns?

Spencer O’Brien: Buns is a handful. He is now a confirmed wolf dog. I had no idea what I was getting into, and it is not something you should do spontaneously, but we were up in Haines at Alaska Heliskiing, my first time ever in Alaska. I was supposed to be in Alaska for three weeks, and I was joking about bringing one of these puppies home, then this huge windstorm came and blew all the snow away. So we pulled the pin to leave early. I spent the next four hours trying to figure out how to import a dog into Canada and drove across the border with him about five hours later. I didn’t realize he was potentially part wolf until awhile later. I started researching wolf dogs and was like, “What have I done?”

Now we’re about four months in and I’m still like, “What have I done?” But he is a real special dog. He’s super smart. And as [Alaska Heliskiing Owner and Operator] Sean Dog [Brownell] says, the Mile 35 dogs have a little something extra. I’m just hoping we can get through these puppy trials.

Have you always been an impulsive person?

No, I’m not an impulsive person at all. I’m just trying to get through the days, like today, where he destroys my $300 duvet for fun, trying to remember that he found me and there’s a reason that he came into my life, so we’re gonna figure it out.

We’re here in Ucluelet, on the west coast of Vancouver Island, with Buns. It’s the middle of summer. Would you normally be snowboarding this

time of year?

When I was competing, I would probably be at Mt. Hood and getting ready to go to Australia and then New Zealand. I did that for 10 years. Now, this is my second summer in Ukee. I’m from the island, and I needed a change of pace from mountain living.

I was born in a small native village called Alert Bay. It’s a tiny island off the northern end of Vancouver Island and about 600 people live there. My mom [Dixie] and all her siblings were born there. My whole extended family still lives there, so we go back quite often. It’s a special place to be from, with so much freedom for children. But when I was 4, we moved to Courtenay. My dad [Brian] wanted us to have better access to schools and sports. We had Mount Washington, the biggest resort on the island. I’d learned to ski at Mount Cain when I was two and kept skiing through childhood, then when I was eight my oldest sister, Meghann (six years older) started snowboarding and so did my middle sister, Avis (three years older). I wanted to be like my sisters. Meghann was really good at snowboarding, and I looked up to her, but we didn’t snowboard together that much because I was so much younger than her, so I ended up snowboarding with my dad most of the time.

“It was a stormy day in early January 2022. Spence and I had been sledding together a ton and almost took the day off. Leanne Pelosi and Jeff Keenan spearheaded this crew, and we figured it would be a good day to get stuck and go have some fun. Jeff and Leanne had both told us their upcoming baby news, so we were already having a good time as a crew when we spotted this pillow popper. Basically, everyone in the crew did a wildcat, with very little convincing. Spence got upside down in the backcountry, her yearly flip checked off the list. We rode pow, got sleds stuck and shot photos till we could hardly see. In the end, we were all glad we didn’t take a rest day. Powder is never a given.” Photo: Tyler Ravelle

Can you tell me more about your dad?

Brian O’Brien loves the mountains. He loves snowboarding more than anyone I’ve ever met, and he instilled that into us. He didn’t work in the winters. He’s a commercial fisherman, so he had time to take us riding. He ended up following me to Whistler when I was a teenager and never left. Now anyone who’s riding the black park in Whistler has met my dad and they’ve seen him hitting jumps and riding rails. He’ll be 70 in February, and he still hits park jumps. We live together in Whistler in the winters and whenever I’m not filming, I’m riding with him.

Was he a boarder before you guys?

No, he was a skier. He taught us all how to snowboard, then he switched and never looked back.

Where did he come from originally?

He was born in Dublin, Ireland, and immigrated to Canada when he was 6 or 7 years old and has never been back.

How did he meet your mom?

He was in Ontario at first, then he says he followed a girl to Vancouver, hitchhiked across the country, and heard about fishing—heard the hub was Alert Bay at the time. He was working there, trying to get his own boat, and he first saw my mom riding her bike down the seawall by the dock. He honked the air horn at her from the boat. It was the only road, so she rode by often, and he kept trying to catch her attention. It worked. When they were together, they worked together every summer, fishing. That’s when I would stay with family in Alert Bay.

In your [forthcoming] movie, Precious Leader Woman, you say you didn’t really engage with Indigenous culture in Alert Bay—why not?

I have memories of being in the Big House and dancing, but I was such a little kid. My uncle’s a carver, there were elements of culture in our life, but once I moved to Courtenay it was minimal. As a family, we weren’t culturally active. We haven’t potlatched for over a hundred years as a family. It’s a big goal of our family to potlatch before my grandmother passes away—she’s in her 80s now. Our heritage was something we knew, but didn’t participate in.

Just the same as I was Irish, I was Native—we never did anything particularly Irish, either. But the older I’ve gotten, the more I’ve become open to learning more about [my heritage], and it’s been really enriching and something I wish I had made space for earlier.

In the scale of learning about my culture, I’m a toddler. My sister Avis has been awesome. Her and Meghann both have done a ton of work to help our family reconnect, and they’ve been very patient with helping me learn and find the parts of our culture that fit for me in my life. Both of my sisters are artists—Avis is a beautiful singer and dancer; Meghann is a weaver. We always joke about trying to find my cultural thing. I’m not sure I have, but for the movie, we went razor clam digging, and I was pretty good at that—so maybe I was a harvester in the past.

“Maybe 7 years old up at Mount Washington [Vancouver Island, BC]. I thought cornrows were cool, obviously. The onesie was a hand-me-down, so I can thank my mom for that piece of fashion. Honestly, this shot is so wrong, it’s right.”—Spencer O’Brien Photo: Brian O’Brien

In the movie you said you were “the perfect example of colonization.” Can you explain that?

When I look at residential schools, they were taking children away from their communities to remove their connection to culture so that future generations would forget and assimilate. I was someone who knew about my heritage, but I had no desire to be a part of it. It was hard to look inward and realize that I was actively pushing it away.

Do you think that’s a result of this systematic effort to remove cultural connections?

For sure. My grandmother’s 84, her father was a chief, and she’s never potlatched. That was taken away from her and it was something that she wasn’t allowed to pass down to her children. When she married my grandfather, who isn’t Native, she lost her rights as an Indigenous person—she was no longer considered Indigenous by the government. My mother wasn’t raised in a culturally active manner, and it trickles down, through generations, that removal from culture.

But there’s a return to our heritage, now. The film was a big reconnection for me. My niece is being raised very rooted in [our] culture, and very sure of who she is. Both of her parents are ensuring that she knows where she comes from. It’s still gonna be up to her what she chooses to do with that, but at least she’s gonna be anchored in that, and it’s not gonna be something she’s searching for later in life. That’s going to lead to very empowered Indigenous people moving forward.

Why do you think there’s this return to Indigenous culture happening for yourself, for new generations?

I think it’s a societal thing. We’re seeing it not just in Indigenous people, but in minority groups everywhere. As a society, recently, we’re allowing people the space to be themselves. Of course, everyone’s journey is different. I’m making these personal discoveries—where does my culture fit for me? The societal shift has made me feel more of a responsibility to be vocal about it and to share my story and to use my platform to elevate my culture and my people. I didn’t want that responsibility before. I would never lie about who I was or my background, but I didn’t broadcast it either. There were times in my life when people were using stereotypes or even being outright racist toward Indigenous people and I wouldn’t say anything—I would just turn the other way.

“I must’ve been 12 here. I remember being stoked on this photo because I wanted to send it to Burton with my sponsor-me letter. I learned methods and wanted to show [older sister] Meghann right away. I’m still running my Shannon Dunn pro model that was a hand-me-down from her. Awful style, but I like to think my method’s improved with the years.”—Spencer O’Brien Photos: Brian O’Brien

How much of your learning process is unpacking trauma versus becoming empowered?

It’s a combination, for sure, and I’ve still got so much to learn. Where does my culture fit for me in this modern world? What Meghann does with her weaving feels like time travel. You’re looking at something from a thousand years ago. The whole culture is like that. The traditions are intact from so long ago through art and language. I’m not an artist and I don’t speak the language, so something’s still missing for me. I’m trying to figure out where my everyday connection lies.

The best advice I got going into my film was from Jess Kimura. Just before we did the first interview, we were talking about [Jess’ 2021 biopic] Learning to Drown, and she said, “Don’t hold back. Be as honest as you can and leave it all on the fucking floor.”

That really hit for me because all the years of doing interviews and having prerecorded answers to everything—I’m going to the Olympics—you become this broken record with answers in the back of your head for everything. For my movie, I didn’t feel so well-spoken; I felt more honest and authentic. It documented my journey into my culture which was happening while we made the film. It opened a lot of doors for me, reconnecting with family and working with Avis on our family tree, and exploring things I hadn’t talked about, or thought about a lot, for the first time.

When did you start the film?

In 2019. My director, Cassie [De Colling], was in Alert Bay working on something else and saw my picture on the wall of fame in the cultural center—it was literally a computer printout with my photo and a little write-up, nominated by my aunt Juanita. We spent at least a year looking for funding. I was interviewing for the Red Bull team manager job. I’d blown my knee, didn’t ride all winter, it was the summer of 2020. I’d lost all my sponsors, the movie wasn’t getting funded… I thought the universe was telling me snowboarding was done and it was time to move on. Then I didn’t get the Red Bull job and two days later, [Canadian telecom giant] Telus funded the movie. I was like, “I’m gonna take this year and give everything I have to this project, to riding in the backcountry, and if it works out, that’s sick. And if not, at least I’m gonna have this cool project to look back on when I’m old and gray.”

The movie itself documents the start of my cultural awakening. We didn’t know what it was about until it was done. If I knew at the time what we were gonna make, I would have never said yes to it because I wouldn’t have been in a place personally or culturally to have wanted to share that part of my story.

Stories find a way to come out. How did it feel at the premieres?

I was scared. In the snowboard world, people don’t talk about their culture much. It’s not something I’ve ever actively tried to hide, but in snowboarding we put so much value on tricks and skill and medals, on video parts—on the accolades—that my personal story never got brought up.

For all the rebel façade, snowboarding can be a pretty conservative space.

It’s interesting to see how resistant people are to applying snowboarding to something greater at times. Everybody just wants this purity to snowboarding. But the last handful of years, we’ve been more willing to tell human stories through snowboarding. Learning to Drown is so beautiful and so vulnerable and still so much about snowboarding, right? There’s a lot of power in story and riders have so much more to offer than just their skill.

“At the end of her first day riding in Alaska, Spencer found her way through convoluted terrain, hit the smaller pillow next to this, then went back and laced the big stack.” Photo: Colin Wiseman

Vulnerability is such a part of snowboarding. I don’t know about you, but I go through a full range of emotions in the mountains. There’s this predominant theme of escapism and bravado, which snowboarding provides, but there’s also a lot more nuance to your experience on a snowboard, and how it relates to your experience in the world, how you’re feeling that day, what’s happening in your life…

It doesn’t matter what type of snowboarding you do, there’s a rollercoaster of emotions. People, for lack of a better word, get addicted to snowboarding because of those highs and lows. It gives you so much, but it also takes a lot away. You can be on top of the world and feel invincible—I can’t compare that feeling to anything else. Then the lows are so damn low. That passion and extremism, when you’re so invested in it, don’t leave a lot of room for middle ground.

And it’s not social, it’s personal.

Yeah. On your own terms. Transitioning from contests, I wondered if I would feel it in the same way without getting to stand on a podium. Then that first run in Alaska felt the same as winning a contest. I realized that high wasn’t necessarily from winning, it’s from doing the run. Whether a trick in the backcountry or a line or winning X Games, it’s the same high.

Did you carry that same performance standard from contests to your backcountry riding?

I still look at snowboarding in a pretty similar way, but it has changed. Doing Natural Selection [in 2022] so soon after retiring from competition, I realized that deep fire to win wasn’t there for me. It was an interesting realization, but it was nice—I’m kind of glad that I’ve shed that layer of myself.

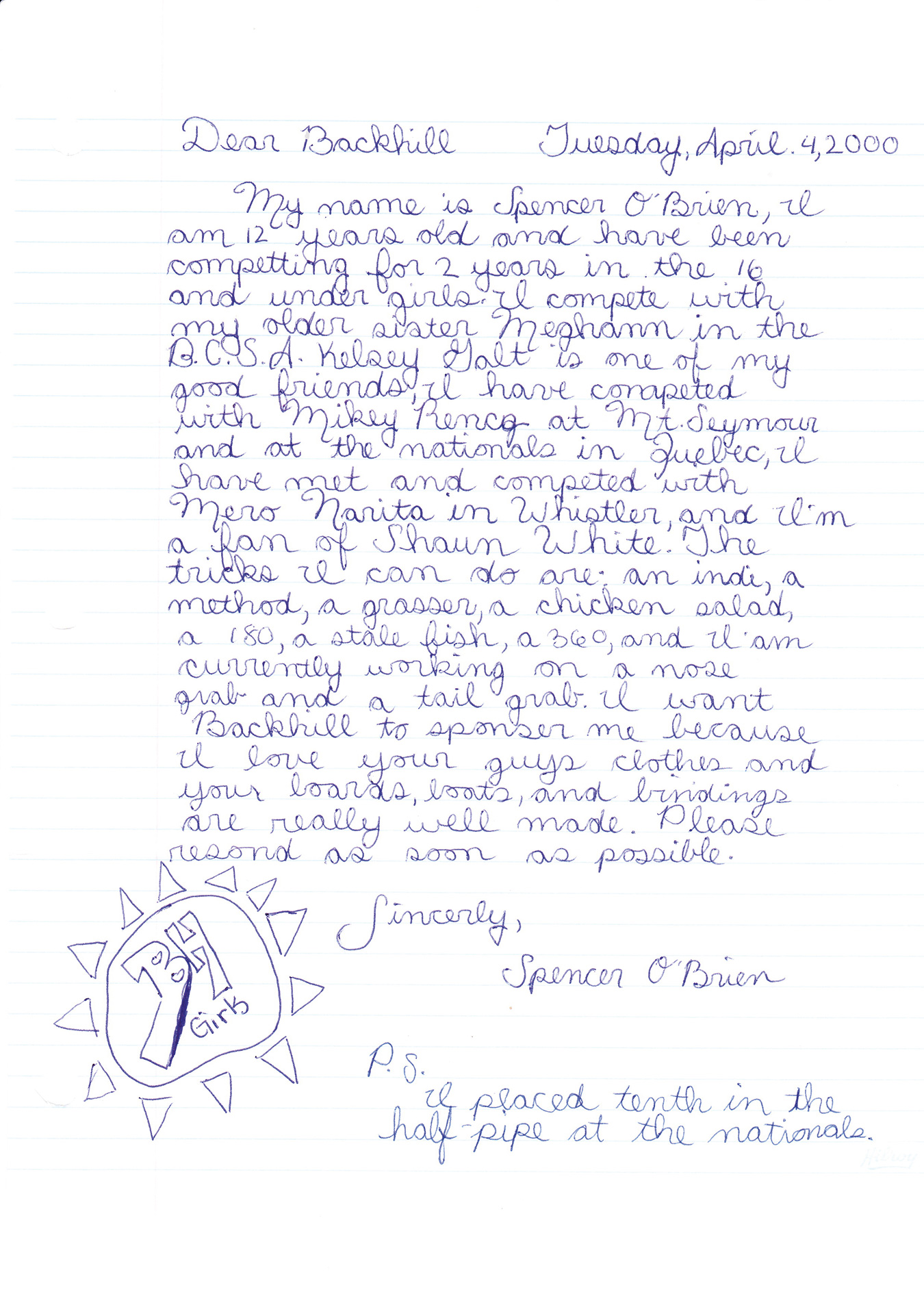

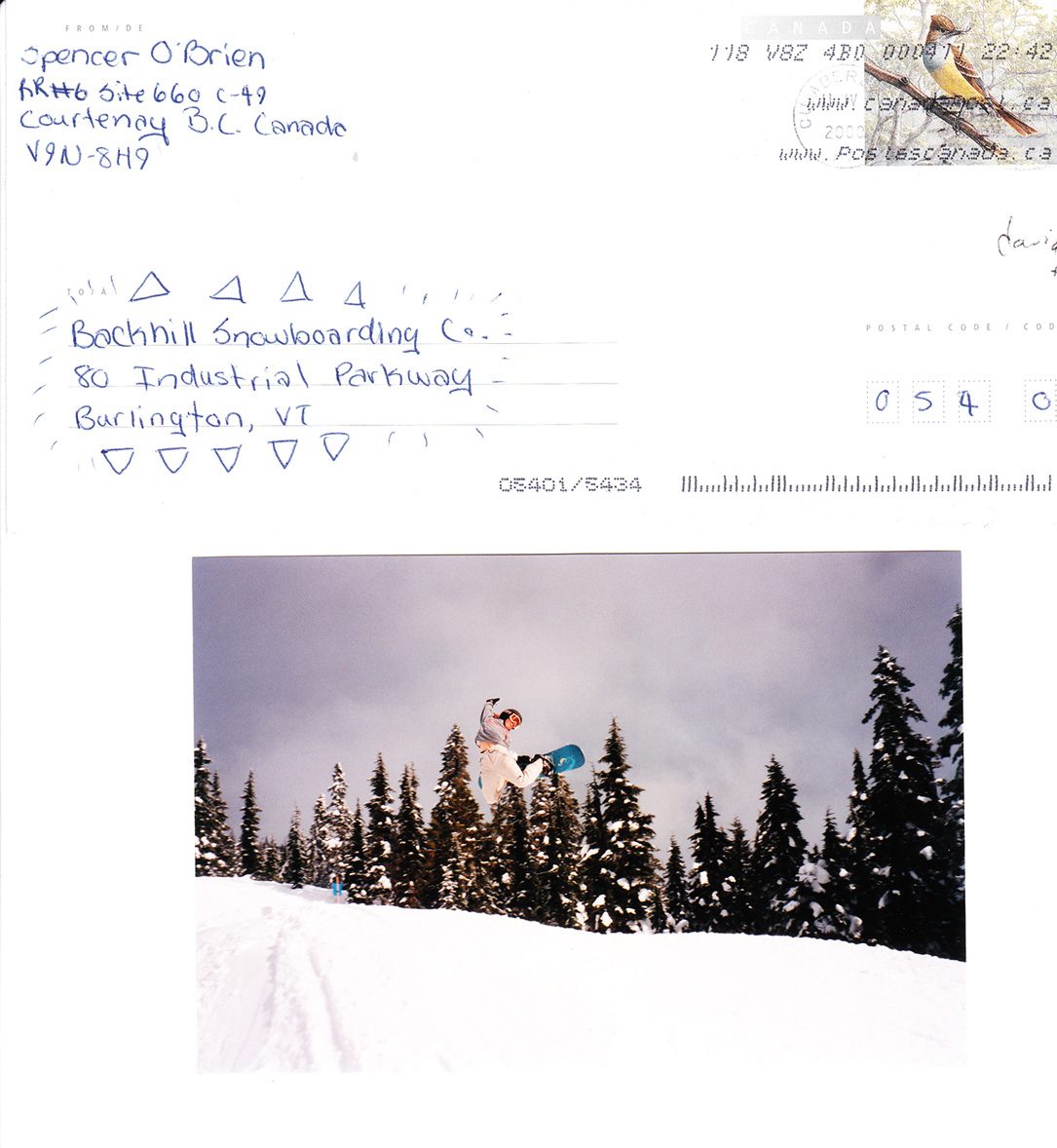

Competitive snowboarding was all you knew for so long—it started with a sponsor-me letter when you were 11 or 12?

I started competing the year after I started riding. Meghann was already doing the circuit. I was 12. I could jump in the truck and go with them. I got last place at every contest. My first day riding a halfpipe was my first-ever halfpipe contest and I was airing off the deck into the flat bottom, literally landing in the middle of the pipe, completely flat. Someone finally was like, “You know, you have to pump the wall. That’s why you have no speed when you get to the first air.”

I was clueless, but I learned a lot. Meghann was sponsored by Rossignol. I really wanted to ride for Burton. So I wrote them a letter, in cursive, because business was done in cursive, that’s pro [laughs]. I was 13 or 14 and I could do a 180 and that was it. I sent the letter in with two photos To Whom It May Concern at the Burton head office in Burlington.

I got a rejection letter, on Burton letterhead, that said thanks for writing in, but you need to start at a regional level—here’s the email for your local rep. They made the mistake of giving me Jeff Martino’s email, then I proceeded to bug him for a year straight until he sponsored me. He became a very big part of my early career and he’s still a big part of my life. He’s like a second dad to me; I love him to death.

“Backside 360 melon in the Whistler, BC, backcountry. This was a memorable midwinter day shooting with the Out of Service crew; three feet of fresh snow, cold temps and nothin’ but sunshine. We started at Breakfast Cliffs and capped it off with some sunset pow turns and a guest appearance from ‘Da Godfather’ Martin Gallant. Spencer has really been pushing it in the backcountry over the past couple of seasons, and it’s fun to watch her put her skills to the test after two decades of slaying parks and competing. She stomps everything. Backcountry Spence has arrived.” Photo: Duncan Sadava

You not only wrote that letter, but you also started keeping a journal, right? How does writing fit into your life? You wrote an important letter after the Olympics in Korea…

I’ve always enjoyed writing. I don’t do enough of it. It was the one thing I was good at in school. When I was competing, it was a ritual for me to write in my journal before I competed—nothing fancy, but the process of putting your thoughts to paper is really powerful and helps manifest them into reality.

Over the years, there’s always been opportunities to do certain pieces here and there, too.

And yeah, most notably is that one from Korea, which I had a lot of help on from Gerhard Gross. He helped me remove some of the anger [laughs]. When there are things that I really care about, the best way for me to articulate how I’m feeling is to write it down. And putting thoughts on paper is a good way to elicit change—to make those thoughts heard. That was my hope with the letter to the IOC after the slopestyle in Korea.

Why did you decide you were the person to say something?

At that point of my career, I was a veteran. I wanted someone to say something and it didn’t seem like anyone was gonna speak up. I talked to a few of the girls about it and asked them how they felt if I wrote something—I ran it by a handful of girls before I put it out; I didn’t want it to just be my voice. But after so many years of riding and fighting for women to have the same [slopestyle] course and to be paid the same and for us to have big air, it felt so demoralizing to be forced to compete in dangerous conditions at the biggest event in sports.

That would never have happened to the men. It didn’t happen to skiing—they didn’t run GS that day. They didn’t run cross-country skiing that day because it was too windy. For snowboarding to be that low in the hierarchy of the Olympics and FIS, that was the last straw for me. I regret not saying something in the moment. I wish I made a big stink because it should not have happened that way. It wasn’t fair to all those women that worked for four years to be there. And that year in women’s slopestyle was a special year. There were a lot of new girls on tour, and a lot of new tricks were happening. That should have been a really exciting event for women and that was taken away from all of us. It didn’t sit right with me and still doesn’t.

The big regret with leaving competition is feeling like I left it in a place that was worse than I found it. When I came into competitive snowboarding, there were so many independent events. X Games was huge, so was the US Open. There was the Global Open Series, O’Neill Evolution, Vans Triple Crowns, TTR—so many snowboarder-owned and driven events. To see this next generation with only FIS as the body of competitive snowboarding, it breaks my heart. There’s so much more, it can be so cool.

“Spencer putting down a solid frontside seven at the Norway X Games big air in Oslo, 2016. I’m always amazed by those city big airs—an urban and surreal surrounding for a cool snowboard event. I named this picture ‘Heavy Metal.’” Photo: Sani Alibabic

Was there a decisive moment when you were done with slopestyle competition?

The film was a big moment because I knew if I was going to do that movie, I wanted to have the riding to back it up. I didn’t want to put something out there with old footage. I knew that if I didn’t commit to that wholeheartedly, I wouldn’t have the shots I would be proud of.

I was coming off a two-year rehab. In that time, the level of riding had gone crazy. I still felt like I had a chance to come back and maybe be competitive, but I had to take a hard look at it and be like, “Do I want to ride backcountry, or do I die on the sword and compete till I can’t anymore?” There were still things I wanted to do [with competition], but I also knew it was my only chance to shift to backcountry riding. I don’t have any regrets about it. It was hard to let go because a big part of my identity and a big way that I experienced snowboarding, and why I love snowboarding, was because I love competition. But riding backcountry is a new challenge. I feel like a beginner again. I’m a kook and I love it.

Were you just burning savings for that first year of filming?

Robin Van Gyn really helped through the “Fabric” series. But my sled and travel expenses for that year came from my savings. I was like, “This is it. I had some good paychecks over the years and I’m gonna invest in myself and either it’s gonna turn into this next chapter of my career or it’s gonna be an awesome thing that I get to look back on and share with my kids one day. And if this is the last year of me being a professional snowboarder, I gave it everything I had. I did something that I always dreamed of doing, which was filming a part in the backcountry.” I knew that I would really regret leaving snowboarding without having done that. Luckily, I now have new sponsors [Arc’Teryx, Smartwool, Korua Shapes, Giro] that support my backcountry riding.

Not only were you fighting injury, but you’ve been managing Rheumatoid Arthritis through all of this as well. Can you explain what that is like?

It was a dark time well before I found out about my RA and then once I did, I had been in chronic pain for months and hadn’t really been speaking to anyone about it. I was training for the [2014 Sochi] Games and very chained to the gym—that was all I did.

Everything in my life surrounded that one goal of going to the Olympics, medaling in the Olympics. At that time, I was injured, and we didn’t know what was wrong with me. I’d spend five or six hours per day with a physio doing everything you could imagine. All this money was getting thrown at me to get better going into the Games. I was very isolated—I have a lot of friends, but I wasn’t making time for them. I was in so much pain I didn’t want to see anyone either. Chronic pain is an interesting thing because you don’t know how bad it is until it goes away. And then it’s like, “Whoa, what was I doing? How was I not screaming from the rooftops about how fucked up my life was?” I couldn’t get out of bed. I couldn’t hold a coffee cup above my head, couldn’t walk downstairs, but I was still going to the gym.

“Brian O’Brien, Spencer’s dad, her biggest fan and supporter. Everything else but a soccer dad. Great guy and a die-hard shredder himself.” Photo: Sani Alibabic

And you still have all this pressure to go chuck 60 feet to ice.

Yeah. Then people are like, “You’ve been training so much, you must be in the best shape of your life.” And I was like, “No, I’m in the worst shape of my life.” I was dealing with this thing that’s invisible, that people can’t see. They don’t understand; I didn’t even know what I had, so I didn’t understand it either.

Looking back, I really regret not seeking more help, not being more vocal about how I was feeling, because I think that’s why it took so long for me to be diagnosed. I wasn’t vocal enough about how much pain I was in and how drastically my quality of life had declined. I couldn’t sleep. I was super depressed.

It was demoralizing to be putting that much into something and have your one tool that you need to do that job be deteriorating. Somehow, we found out what I had, and I got medicated two months before the Games. I ended up on some crazy drugs to get me there to compete. Depsite everything, I actually felt really good at those Olympics. [Not medaling] is harder for me to swallow in Korea because I feel like I let myself down in Sochi. I had everything I needed to medal there and it just didn’t come together on that day. But on the flip side of that, after everything I went through, I got there. Even though I didn’t get the fairytale ending, I learned a lot about myself through figuring out the RA.

What did you learn?

I’m very stubborn [laughs]. It showed me how much snowboarding means to me, and that it wasn’t just about competition. The idea of not being able to snowboard again wasn’t an option. It showed me that I was probably running a little bit too close to empty all the time. I was probably asking too much of my body. It taught me to be more aware of what my body was trying to tell me. It also taught me that I’m a lot stronger than I thought I was.

Why did you keep it quiet?

The only thing I wanted people to care about was how good I was at snowboarding. How many medals did I have? My self-worth was very wrapped up in in my competitive identity. The idea of being a snowboarder with an illness, especially at an Olympics where everything is hyped up, was just too much for me. I needed to pretend like I wasn’t sick to get through those Games so being public with it wasn’t an option for me. The Games come with so much pressure and media scrutiny and, all of a sudden, after 10 years, in the sport in which no one wanted to know about my culture, I was Canada’s Indigenous snowboarder. That was a role that I wasn’t prepared for and that I didn’t know how to speak to, and it made me very, very uncomfortable. On top of that, I didn’t want to be the arthritic Indigenous snowboarder. I just wanted to snowboard.

Also, I’m not good at asking for help and I’m not good at being vulnerable. I didn’t even tell a lot of my close friends. It probably wasn’t the best way to deal with it. I probably would have found a lot of allyship, support and compassion if I had just been open. But it’s scary to be open, and all the shit that comes with that, right?

I didn’t even begin to unpack or process my diagnosis until well after the Olympics were over. I needed to put the blinders on and just get that job done before I could be like, “OK, what is this lifelong illness, how do I manage it? How does this change my life?”

“Switch backside 180 at the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, Korea. Spencer has been holding it down for almost two decades. She dealt with injuries and health problems the season leading into the games but still made it into the finals of the Olympics Big Air and rocked as she always does. Nothing but respect for Spencer, for what she has accomplished in the past and for what’s still to come.” Photos: Sani Alibabic

How do you feel now?

I am very good right now with my RA. I’ve been lucky that it’s stayed consistent for me. I have been on the same medication for about six years now, and it’s just a once-per-month injection with very minimal side effects. I feel more or less completely normal. I feel lucky because a lot of people don’t find that kind of relief.

And now you’re riding backcountry and succeeding. Precious Leader Woman is amazing. Where does the name of the film come from?

We decided to name the film Precious Leader Woman early on because it’s the translation of my Haida name [K’ul Jaad Kuuyas] into English. My Kwak’wala name is ‘Ma̱lx̱tłu’g̱a, or Mountain Goat Woman.

The names are given by the matriarch of your clan, and often they’re based off people from your family. With our family tree, we didn’t have very many names because my great grandmother left Haida Gwaii when she was 14 and never went back. We just started going back up there in the past decade.

A lot of times if you resemble an elder, you’ll inherit their name, but you’ll share it with them. Leona felt like I didn’t fit any of the names we had in our family, so she made me my name and gifted it to me. There is a lot of honor and responsibility in the names so it’s important to me that I live up to my name. I feel like one day [my niece] K’yuusda Rose might share my name because she’s kind of like me.

That’s Avis’ daughter, right? How has your relationship with your siblings grown recently?

My relationship with my siblings has been interesting. Growing up snowboarding, I always looked up to Meghann. I was grateful to be following her footsteps, in the very early days of my career, and watch her ride backcountry. I’m sure that’s a big reason why I always wanted to do that even after years of competing, and years after she retired, she still left me footprints.

Me and Avis are extremely different people—polar opposites. All three of us are like a triangle, so far apart. I wasn’t super close with my family for a lot of my life, but for some reason, when Avis got pregnant, that really shifted for me and her. It wasn’t that we had a bad relationship, we just weren’t close, but we’ve become extremely close since she had K’yuusda, which has been really special. K’yuusda has been such a gift to our family and it’s really cool to see your siblings step into parenthood. Now Meghann is pregnant and I’m very excited to see her become a mother.

When I was competing, I was so busy and focused on snowboarding that I had to be selfish a lot of the time, and I definitely had no problems doing that. I missed a lot of big things for my family because I was focused on what I was doing, that, at the time, felt important to me. Now it’s nice to be at a place where family is playing a lot bigger of a role than it ever has before. And I have my sisters to thank for that.

Spencer in the Whistler, BC backcountry. Photo: Mason Mashon