Interview

Travis Parker

To Be Healed: Day by Day with Travis Parker

ABOVE An end-of-day portrait of Travis Parker, July 2018 at Timberline Lodge, OR. Travis called Mt. Hood home for plenty of summers throughout his professional career–just another spot on a long list of locations where Travis has lived. Photo: Ben Shanks Kindlon

Despite his 42 years of age, it’s Travis youthful energy on hill that gets me. He lowers his goggles, surveys the slope, then claps and rubs his hands together in excitement. He’s happy, and it’s infectious. On the surface, Travis displays the same frolicsome demeanor the snowboard world grew to know and love at the turn of the millennium, when he emerged as one of the most charismatic and progressive riders of his time. But there’s much more to Travis than some laughs and a bag of tricks.

Wisdom comes from experience, and Travis has a lot of both. It shocked many when he quit snowboarding professionally in 2010, at a time when he still held a lot of influence. After lapping the lifts till close, Travis sat down and filled me in on what happened, and how he’s been since. True to form, he came across colorfully, but in a different shade than before. The light Travis had to shed on his current approach to life proved to be just as powerful, timeless and inspiring as his riding ever was.

The Snowboarder’s Journal: Let’s start from the top.

Travis Parker: I was born in Houston, in Harris County. I bounced around Texas—San Antonio for a bit, and then a little town called Jonestown. There’s a lake there called Lake Travis. My brother, Rivers Lane Parker, and I both had Diamondbacks [bikes]; he had a black one and I had a blue one. We just ripped around, man. You know how kids are. We’d go everywhere, build forts. We’d dig ditches and put cactus in them, and then cover them with twigs to try and get each other to walk over it. That was pretty bad.

Rivers is my only brother. My parents’ names are Carol Kennerly and Joel Parker—Charles Joel Parker. My dad was an Eagle Scout; he taught us a lot about scouting, and, gosh, we learned how to start fires and cook vegetables in tinfoil and camp out. My mom took us arrowhead hunting and stuff, and we found some really cool ones. It was a good time just being a kid, skateboarding, rollerblading, video games, movies, taking the bus—I used to take the transit system from Jonestown all the way into downtown Austin to skateboard. I was like 10, 11 years old. My brother and I had a lot of freedom; my parents were always cool.

above “My first trip with Travis Parker was to Chile in 2010. Travis had just landed a comeback spot on the K2 Snowboarding team and was frothing harder than ever to ride. Although the snow wasn’t perfect, Travis was riding really fast and laying down epic turns on springlike corduroy.”Photo: Mike Yoshida

What did they do for work?

At that point in my life my dad was selling supplies for Vaughn Wire and Cable. My mom was working for Gourmet Gal as a caterer, and she worked at 3M doing shipping and receiving. She had a lot of different jobs, but I think her favorite job was being a caterer because they made some really cool stuff. She even got to cater a dinner for Prince Charles and Lady Diana. They made this white chocolate swan and put a bunch of berries in it, and she brought the swan home for us to have some white chocolate in the fridge.

I grew up in Texas until I was about 13 or 14, kind of moving back and forth between my dad’s in Wimberley [TX] and my mom’s in Jonestown. It was around then that I saw mogul skiing on the Olympics and was like, “I’ve gotta learn to ski.” My aunt Nancy lived in Montana, and I got an opportunity to move up to Whitefish. I went to live with Aunt Nancy, Uncle Carlos, and my cousins Canyon and Chase. They’re like brothers to me. I was a freshman in high school, I believe it was ’89-’90, so I’d just turned 14. I had never seen a mountain before. I’d seen hills, but never mountains. I just couldn’t believe that mountains could be that big, and that they were just, there, ya know? It was so cool.

How’d you learn to ride those mountains?

My aunt got me ski lessons for the first four or five weeks I was there, and I liked skiing a lot. I got a pair of Line boots, a pair of Rossignol skis, poles, and during preseason we’d go up cross-country skiing. But then my uncle brought a snowboard to his shop, a Gnu Kinetic 168. When I tried it, I just instantly connected it to all my skateboard days. I turned to make a stop and was like, “I can shred,” because that’s the sound it made—It made a shredding sound. The rest of the year I had snowboard lessons around Chair 3, which is like a lower-mountain beginner slope [at Whitefish Mountain Resort]. Jesse Grandkoski and I used to ride Chair 3 all day, or go up night skiing and just lap it. We were pretty inseparable at a young age, just total pals, man, the best of friends, especially on hill.

above left to right “My tee-ball portrait when I played for the Comanches back in 1981. We had really good coaches that year because I remember hitting a lot of baseballs, getting really excited, and rounding a lot of bases. It wasn’t serious yet—it was ‘just have fun out there, kid’ baseball.”

—Travis Parker

“A frontside air shot on Big Mountain in Whitefish, MT, during the winter of ’90/’91. I had a fresh coat of wax from my uncle’s ski shop called ‘Snowfrog’ and hand-me-down clothes from my cousin Jord to keep me warm and dry. It was the best Christmas of my life.”—Travis Parker

Photos: Travis Parker Archives

Did you meet Jesse at the mountain?

I met Jesse at school in Whitefish. He had the Tony Hawk bangs, and was a super-smart dude. He and Dusty Ostler and Cody Shining were influential in getting me into snowboarding. I remember going to high school dances with them, and in between dancing with girls we’d all talk about snowboarding and how it’s the best thing ever. Whitefish is a really rolly mountain with some cat-track jumps, and when there’s powder, it’s great. Depending on the day we’d go jump cliffs, and if it was hard-packed we’d go hit the rollers and jumps. We got to be free and have fun on that mountain. Definitely had some crashes, too. Woo-wee.

My uncle owned a ski and snowboard shop called Snow Frog, and he let us have a team—Team Snow Frog. Andrew Crawford was on Team Snow Frog, and so was Jesse Grandkoski, and I think Bill Sarno too. We would go to regional competitions and meet some of the other Montana snowboarders who had help from sponsors. I ended up going to a contest near Missoula and competing against some of the other up-and-coming riders in the scene at a mountain called Ski Bowl. I didn’t do so good in the competition because I didn’t catch air like some of the other guys, but being there was awesome because I got to see what it took to be at that next level. It opened my perspective to it being possible to do this. I knew it wasn’t really the real world, but I wanted to pursue the dream.

Were you filming for any videos in Whitefish?

We did, through Polar Bear Productions with one of our mentors, James Fisher. He was a super-cool guy, and he and his wife, whose name I can’t remember, were both filmers and photographers. They were older than us and filmed some big-time pros that came through, which gave us a little bit of something to dream for. I started getting product flow from Burning Snow outerwear and Newschool Snowboards, and then I got in a local magazine in a Burning Snow ad—my first ad.

I graduated high school and started to go to Flathead Valley Community College [in Kalispell, MT], but when I was in college all I wanted to do was be at the mountain. Jesse Grandkoski was living in Colorado Springs and I wanted to move there because Colorado was the scene to be a pro. So I went and stayed in his dorm. Some of the guys there let me take classes under their names at Colorado College. It was probably against the law, but I did it anyways. I was kind of a rebel, you know? That’s what snowboarders were. We were rewarded for being rebels.

From there, I got an opportunity to move to Vail, first working as a parking-lot attendant, then at the Sonnenalp [Hotel] restaurant bussing tables. I took a bus there at 4 every morning. One day I missed the bus, and I was wearing all these nice wool clothes that I had to work in at the restaurant. I ended up running to work in the pouring rain, the whole time thinking, “I do not want to do this. I just want to be a pro snowboarder.”

I saw guys like Ali Goulet, Stevie Alters, Russell Winfield, and awesome female riders like Rhonda Doyle and Barrett Christy making it, and I was like, “I can do this.” I ended up meeting Josh Heminger, whose dad had skied for K2 for a long time. Josh snowboarded for K2 and said he would get me in touch with the people there. At the time, K2 wanted people to promote their Clicker bindings and I said I’d do it. That was my window. K2 flew me to BC to shoot for their catalogue and I got to meet Eric Berger, the photographer, and people like Brian Savard—a super-cool mentor who planted trees in the summer. I ended up living with some of them in Utah and started to film more. I got lucky man, I just got lucky.

Doug Hollenbeck, a windsurf photographer, got me some shots and my first full page in Transworld. That was a big deal. I was on a K2 board and K2 Clickers, so they advanced me through their program and I started getting better contracts. Gosh, K2 just gave me all the opportunity in the world to be my best. I was riding those Clickers for probably three or four years, first without a highback and then they went to Clicker HB with highbacks. We did a lot of testing, and a lot of snowboarding on those Clickers.

above “November 2004 at the private DC Mountain Lab facility in Park City, UT. Grinding through this natural rock wall ride was even more impressive than it looks in the photo.” Photo: Nate Christenson

What did you do over the summer during those years?

I spent my summers at Mt. Hood, learning all the new tricks. The first time I came out to Hood was on a Greyhound with a tent and like 50 bucks. I popped my tent and hitchhiked up to the mountain every day, meeting all kinds of cool people. That’s when I was 19 or 20. After I was introduced to K2, I started staying at the K2 house, and Brian Harper, who ran Windell’s dig crew, let me on to dig and ride. I was on the rake for a while and after that I was a coach, you know, driving buses and all that. I grew fast.

Were you breaking in with some bigger production crews at that point?

By then I was riding for DC, Smith, Sessions and coming up on being pro for K2. I was starting to do better in some contests and getting some shots in videos, riding and traveling a lot. I had a really big break with the Sessions video, Viva Sessions (1999), and while I was riding for them they got me on X Games. I did two at Mt. Snow [VT] (2000 and 2001). By that time, I had a good photo incentive and video incentive. I was getting shots in all the magazines, and getting a decent paycheck. I’d live summers here at Hood and winters in Utah, until I moved to Lake Tahoe [CA], and was riding Boreal.

I started getting some shots in the Standard Films movies, too. Those were big films, and my head started blowing up a little, you know? I went out with TB7 (1997), TB8 (1998), TB9 (1999) and TB10 (2000), but after several years, I kind of reached the end of my time with Standard Films. Mike [Hatchett, Standard Films founder and director] didn’t think I would be an Alaskan snowboarder, and that’s not saying anything negative on him, he was just being realistic—this one avalanche out there really spooked me. He kind of said I didn’t have a future with Standard Films and it was sad, but at the same time I knew my career wasn’t over. I knew I had more to do.

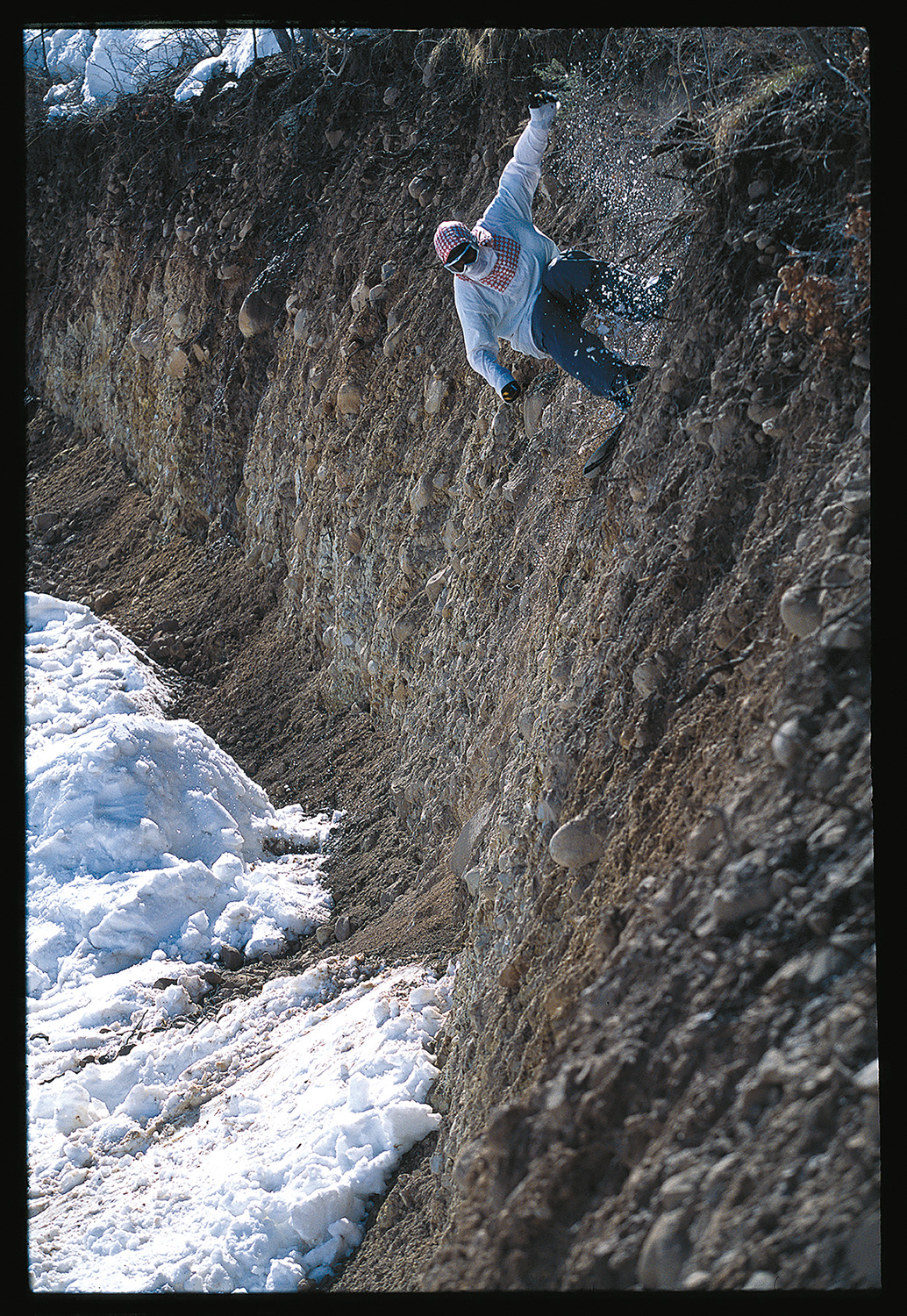

above “Backside 180, Stanley, ID, circa 2003. This was such a fun backcountry area to explore. During the Robot Food years, we spent several weeks out there every winter.” Photo: Nate Christenson

What came next?

I was living on Stockholm Way in Lake Tahoe—up in Donner Summit—and I ended up getting a computer with Jussi Oksanen and [filmmaker] Jess Gibson, right around the time that Final Cut Pro [video-editing software] came out. Our timing was right on.

Kevin Jones was our neighbor down the street on Stockholm Way. He said something about robots eating old people’s medicine for food and everybody started laughing because it was a big joke from this popular skit on Saturday Night Live. Someone said, “Robot Food” and all our eyes lit up. Robot Food was a perfect name for our crew because you can stick a tape in your VCR and it totally eats it. We were making food for snowboarders every year, for them to be like, “OK, this year we got this video. What’s for next year’s video?”

Pierre Wikberg was another filmmaker and friend, so we all started an email loop, talking among ourselves and getting sponsor money rallied to pay for a Robot Food movie. We had connections with different marketing departments, they were supportive of us, and I’m so thankful for that. We ended up making something I think was completely different for the time. It was so awesome and fun, but also progressive, you know? That was Afterbang (2002). Big year, a lot of travel as well—Norway, Sweden, all over Tahoe and Utah and Colorado. Red Mountain Pass [CO] was a big stop for us; we’d go there all the time. Lame (2003) was the very next year, and then Afterlame (2004) after that.

above “There was once an ugly time in snowboarding when ski companies and snowboard companies didn’t play nice in the proverbial sandbox together. K2 Snowboarding was part of a ski company that was making a hard run at being number one in snowboarding. Rather than run away from the fact the K2 also made skis and inline skates, the professional snowboard team lien-ed into this obvious weakness and embraced it only the way a confident snowboarder can. Under the creative leadership of Travis Parker, the team booted up and unleashed their professional athleticism and style for this two-page spread print ad. Left to right: Wille Yli-Luoma, Katrina Warnick, Louie Fountain, Travis Parker, Brian Savard and Bobby Meeks.” Photo: Trevor Graves

What was it like filming with the Robot Food crew?

Real professional, real hardworking, real we-gotta-do-this-right. It was awesome. It was a freakin’ totally cool snowboard club. Part of Robot Food was to show the fun part of snowboarding, and I was seriously having fun. I loved it. I wish it never ended.

But after that trilogy all of us moved to different places or started having families. Our email circle fell apart. It’s kind of like a band, you know? How do you keep a band together? In hindsight, who knows, it probably wasn’t the right thing to do, because [Chris] Englesman was like, “Let’s keep doing this.” He’s always been a leader, so it probably would have been smart.

How does cofounding Airblaster tie into the picture?

Around the beginning of when we started filming Lame is when we started Airblaster, in 2002. I moved out of Lake Tahoe to Portland [OR], where my boards were being designed at Nemo Design. I had a pro-model board with K2, and every year I got to design something. My childhood friend was my roommate in Portland: Jesse Grandkoski, star soccer player, one of the best snowboarders—a peer that has always been so level-headed and sharp as a tack. He said, “Trav, do you want to start a company? We’ll make a clothing brand, then we’ll have snowboarding for the rest of our lives.”

I said OK and started putting money into it, promoting it in Lame and Afterlame. We had a team of myself, Jesse and Paul Miller, who is also a freaking genius. I would be out in the field promoting, Paul was business administration with computers, and Jesse was working with patterns, cutting and sewing, actually creating the articles of clothes. Airblaster started making movies—December (2005) was one of the first big ones to come out. And DC Mountain Lab (2005) was also being filmed right around the time Afterlame came out.

above “March 2006 in Spokane, WA. The month-long Bike Car adventure was just getting started. I’m sure Travis and Louie Fountain are laughing about how tired they are only a few days into the journey.” Photo: Nate Christenson

Where was the DC Mountain Lab?

Park City, UT. You would take Jeremy Ranch Road across from Park City, go up into the mountains, and that’s where it’d be. Man, it was cool. I felt very welcome and I’m very thankful I was a part of the Block family’s endeavors there. They really did a lot for us. Lockers with our names on ’em, our own rooms, food, coffee, movies, video games, snowboarding. They’d take us out to dinner sometimes, too. I probably didn’t take advantage of it as much as I should have in hindsight. I was just so busy with everything.

I was spoiled rotten. Spoiled rotten, spoiled rotten. I have these moments when I’m like, “Meh, wah,” but it’s only because I had it so dang good before. It must be so annoying, so I try to keep my mouth shut because I was just so blessed with opportunities, and I’m so thankful for everything.

People are amazing. That we’re just a part of these amazing groups, just to sell and ride these fun products—what a neat industry. I love being a part of this industry. I just made a graphic for an Airblaster Ninja Suit; I’m excited about that. It’s a bunch of yoga poses, people stretching in Ninja Suits. I really enjoyed designing it and am thankful Jesse invited me to do that.

You went from filming video parts yearly to essentially not filming at all around 2009. What happened?

That was around the first time I thought, “What am I gonna do beyond this?” And that moment struck me hard. I was starting to go to college at Lake Tahoe Community College and it got to the point where I thought I wanted to really pursue it. I didn’t feel right being a pro snowboarder and doing that at the same time. I felt like I wasn’t doing either one enough. So, I flew out to see [DC co-founder] Ken Block and told him I wanted to study art and thanked him for everything. I was riding for Capita at that time and let them know, and thanked them so much for everything, too, but told them I was done. I think that was in 2010. I remember Todd Richards was like, “What are you doing, man? You’re at the top of your game. You don’t need to be winding down; you need to be going more.”

But it’s much more complex than that. I dealt a lot with mental health during that whole period, and there was a whole shift in my career when I had a realization about my mental health. Over the years I’ve been trying to come to terms with all that, and I’ve worked out a lot. I have the capability of having extreme highs, but I also have the capability of having extreme lows. I can dive into some pretty dark bits of my mind. I’ve always been a hypochondriac. I didn’t know if I was just a hypochondriac with all this stuff, or if it’s just something people go through, but I had a talk with my dad and he said, “I don’t know about you son, but this stuff is real.” There were times when I just couldn’t get a grip, man. And it was real. I needed a timeout.

I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder type 2; my dad was type 1. Mental health is serious stuff and I’m so grateful for all my doctors, psychologists and psychiatrists. It’s been helpful to have professionals to work with, and you know, I do well with talk therapy.

above “November 2004 at the DC Mountain Lab. Travis popping a backside air on the wall ride. Our own private lift and park designed by Chris ‘Gunny’ Gunnarson and Snow Park Technologies. Need I say more? Thanks, Ken Block!” Photo: Nate Christenson

Is that why you chose to stop drinking?

I’ve been on and off with sobriety throughout my whole career, and my whole adult life. I drank a lot when I was 16, 17, 18, so much so that I poisoned myself with vodka when I was 16. I couldn’t move my hands, couldn’t open the door. My aunt had to take me to the hospital.

I’d go from drinking too much to cutting it off for a few months, then going back to it. The heaviest I drank was probably in my mid-30s, after my pro snowboard career was over. My money was starting to dwindle, and I was about to drink my money away. I’d go the bar and get pretty tipsy, man. We’d be dancing and stuff, but still. Ah, jeez, if not dancing, then just emotional about something. Emotional about a good life, you know? But I went to wind turbine technician school and realized I better sober up if I’m gonna go start a new career.

That’s all part of mental health, I think, becoming sober and having those realizations. It’s not easy being sober, because you’ve got to realize who the hell you were when you weren’t sober, and what kind of decisions you made. “What kind of human being was I? How was I in relationships?” Living in the past a little bit, but also learning to accept those things and move on to become a better person, a better version of yourself. I’m just so lucky I have family members who are showing me how to recover. I have been in recovery, and still am.

Are you willing to share that?

The mental health stigma is… By saying, “Are you willing to share that?” it’s a choice I make. Am I strong enough of a person to face this reality, that mental health and recovery is a part of my life and I can be open about it? I’ve accomplished so much in my life—I think I can face this. So, yeah. I think it’s a positive and healthy thing to share.

It’s real, man. There’s a lot to deal with in your life. I’m just thankful I have the tools to take it day by day.

above “Travis is a character. Despite only riding a few times per year, when he drops in, he still displays the style and energy you’d expect from him. Here’s Travis cranking a method in the Timberline Lodge terrain park shortly after raising his hands toward the sky and audibly praising God for the snow, mountains and weather we enjoyed on this cloudless day in July 2018.” Photo: Ben Shanks Kindlon

How are you feeling overall?

Overall, pretty good. I miss being social. I miss a lot of my friendships in the snowboard world, where I was having the time, and the high, of my life. But I’ve also really come to appreciate things like a nice walk after a day’s work. I currently work a little more than 60 hours per week between grinding hitches at Premiere Manufacturing Company and as a technician at ECO Maids. I’ve become a better cook, too. I’d like to read more, and study more. I’ve done quite a bit of reading and studying in the past few years, but not to the extent I want to be. I read the Bible cover to cover, I study it, and I’ve read some of the Torah. I don’t necessarily go to church, but I study and pray all the time. I’m just so thankful every day, it gives me a way to meditate.

I do have regret. I regret ever saying anything negative about the sport of snowboarding, which I love. There were times when I was sad and angry and throwing a fit about how I wanted my career to go, but it was all very trivial. Snowboarding is a great part of my life.

I regret that some of my friendships have gone out the window. When I was drinking, I thought it was great because I was way more social. I probably had more girlfriends when I drank, but I should have had just one girlfriend, you know? I could have had better relationships throughout my whole life, but again I hope I learned from them and became a better person. I regret some of this debt I’ve accrued from buying too many cars. But I’ve learned something from all my mistakes, and I’m thankful I’m in recovery.

I’d like to heal. Really, I’d like to be healed. I want to just get out of the wheelchair and walk. I don’t know if it’s like that, though. I have mental health issues that I deal with every day in my life. And as far as drinking, I loved it. I loved beer and I loved whiskey, but I don’t do it anymore. I’ve made it a habit to not do it, and it’s not even an issue anymore. I have other habits now, like going for walks, getting good at my jobs, doing sit-ups, reading and going snowboarding when I can. I’m just trying to be a better version of T.P. here, the best version of myself.